Range Rover at 50: Remembering the 1970 launch and how the upmarket 4x4 changed the game

Fifty years ago Land Rover launched a 4x4 with creature comforts – it was a revolutionary idea, and Eric Dymock was there

ROVER publicists were ever-unsettled by Land Rover, but in the first week of June 50 years ago, I found them in a new quandary. “One of Britain’s fine cars”, as the ads portrayed the Rover road car, had always sold without saying very much. Understatement for quiet aristocrats. Since 1948, Land Rovers had been agricultural or military, so not much needed to be said about them either. On quiet farms, or in deserts, jungles and swamps, Land Rovers spoke for themselves.

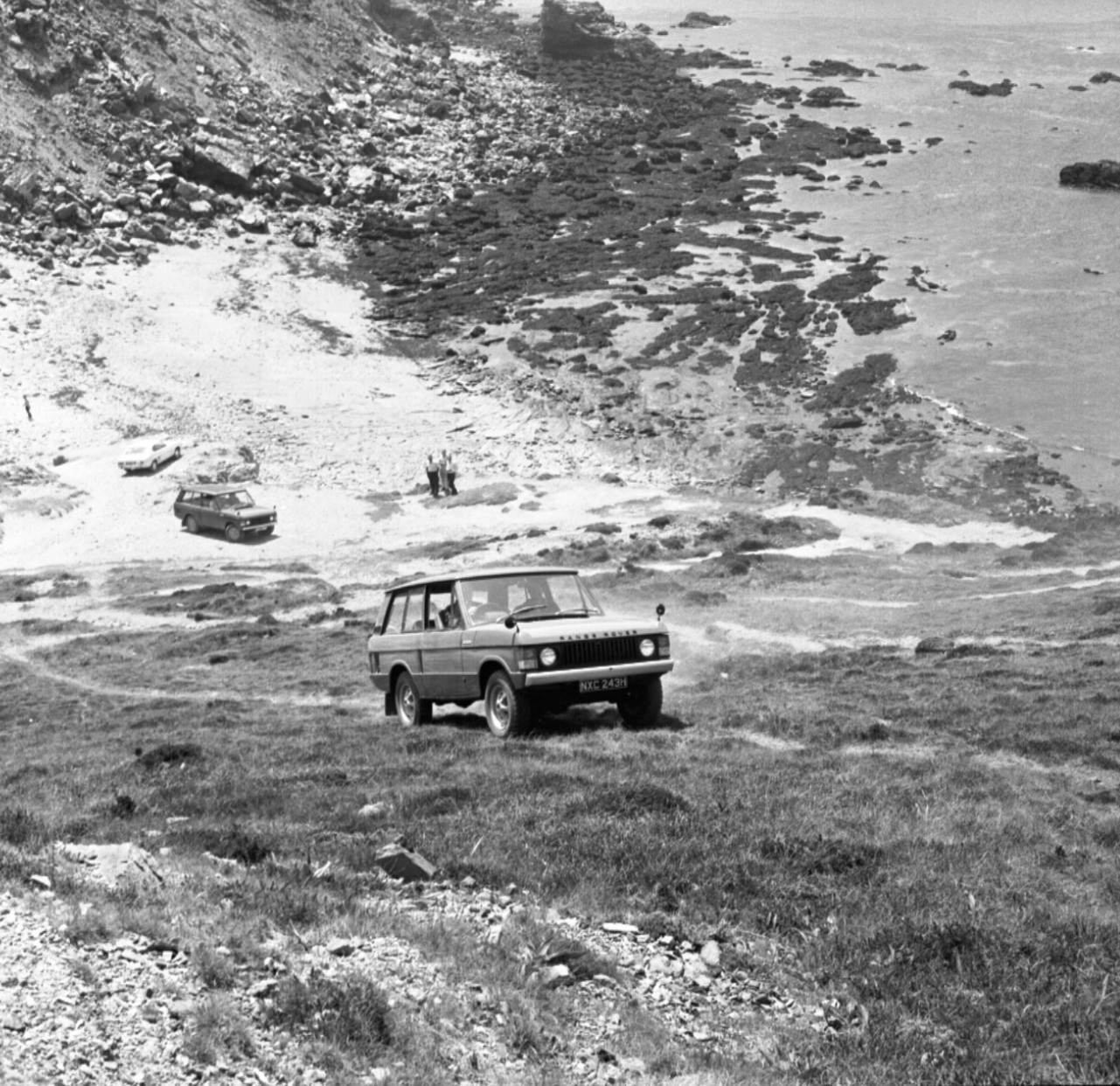

But now, addressing the great and good of Fleet Street on the 10.10 from Paddington to Penzance, the new Range Rover’s press material came with all the weight of a Post Office announcement.

“Not for publication until Wednesday, 17th June, 1970.”

No equivocation there.

“A revolutionary new model combining the luxury and comfort of the world famous Rover saloon car range, the acceleration and handling characteristics of many high performance cars, the stylish body of an estate car, and the ruggedness, durability and cross-country versatility of the renowned Land-Rover, is announced by the Rover Company.”

Perfectly true but scarcely succinct. The company didn’t even appear sure what to call it, beyond Range Rover, that is. It tried “estate car” and “Station Wagon”, sometimes with capitals, sometimes without. The vehicle was a “highly competitive contender for the valuable and fast growing four-wheel-drive ‘leisure’ market”, whatever that was. The company was on firmer ground with a trendy title. A car “For all reasons” trailed Robert Bolt’s screenplay for A Man for All Seasons, a film still doing the cinema rounds. It had a familiar ring.

Yet convincing Fleet Street hacks would take more than Post Office English and a posh hotel in Mawnan Smith.

I joined in almost by chance. I was new. After three years of road-testing at The Motor, I knew about mph and mpg, nought to 60 and maximum speeds, and how cars behaved on the road and track, until my slide rule (remember slide rules – before calculators?) caught me out and I was “let go” to try my luck elsewhere.

“Cornwall was sunlit and calm. Land’s End trial hills such as Beggars Roost beckoned as a test route”

As a new freelance writer, I had been sent by Michael Heseltine’s trendy Town magazine to interview Enzo Ferrari. We did his new rival Ferruccio Lamborghini the same week with the prototype V12.

My main gig was as a motor-racing correspondent for a broadsheet, but as its own motoring writer was doing something else that week, I won the invitation to the Meudon hotel, near Falmouth, to try out this new Range Rover thing. The trip came between the Monaco Grand Prix and a busy June, with the Belgian Grand Prix, Le Mans 24 Hours and the Dutch Grand Prix at weekends.

It was always safer on test drives to team up with somebody you knew. John Blunsden, motor racing correspondent of The Times, was on the train. We trusted one another’s driving and sat in first class behind Inter-City Great Western D800 diesels, learning, alas, sad news. Bruce McLaren had died the previous day at Goodwood while testing a Can-Am car. We both knew him well. It was not a good start.

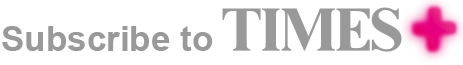

We were bussed into Meudon hotel’s 8½ acres of subtropical gardens, its giant rhubarb plants leading to Bream Cove and a line of Range Rovers. Cornwall was sunlit and calm. Land’s End trial hills such as Beggars Roost beckoned as a test route.

We knew plans for Road Rovers went back to 1953, and how prototypes got overweight and abandoned. We had tested the Rover 2000 and were familiar with the preoccupations of the designer Charles Spencer King (1925-2010), one of the dynasty that ran Rover. A reserved, gifted, empirical engineer, “Spen” King – a wartime apprentice at Rolls-Royce – made space in the 2000 for a gas turbine. It never got one, but its appliqué body panels on a stiff frame provided an exemplary ride and handling. King’s genius was never appreciated in the nascent British Leyland.

Another of the dynasty, William Martin-Hurst, had invented a market research department under the economist Graham Bannock, who said Land Rover would expand only at the leisure, high-priced end of the market. Sales to the military and police were fine, but a generation of private buyers towing boats, caravans and horseboxes did not like harshly sprung Land Rovers (which later became known as the Defender).

A visit to America in 1965 convinced Bannock that sport-utility vehicles (SUVs) such as the Jeep Wagoneer, International Harvester Scout and Ford Bronco were laying sophisticated wheel tracks. The Road Rover dreams of the 1950s were worth reviving, he realised, so King began work in 1966.

Harold Wilson’s government speeded things up. Purchase tax was hitting car sales. Military withdrawal east of Suez, November’s financial crisis and devaluation affecting defence spending proved Bannock right. Some sort of SUV, with the long-travel, low-rate coil springing King had invented for the Rover 2000, had to take up the slack. A trial drive of a 2000 in a bumpy field was convincing. There was already a V8 Land Rover from which the gutsy engine could be pinched.

Blunsden and I took off in the product of Spen’s efforts and drove cheerfully round a prescribed route past Goonhilly Downs. In those days, the car-maker always had chase vehicles in attendance in case a journalist got lost, strayed off to a pub (it wasn’t unknown) or crashed (that wasn’t unknown either) or a car failed. After a short time, we concluded that here, at last, was something like a Lunar Rover. An extraterrestrial exploring Earth would have had to invent it. This was the best combination of on and off-road, with high clearance and astonishing agility.

On roads, the Range Rover was comfortable, roomy and fast. You could drive it into a field and, provided it was not deeply ploughed, you need scarcely slacken speed. Bumps disappeared up the marshmallow springs. Land Rover had long believed a harsh ride slowed drivers, which meant they didn’t break anything. King was convinced that supple long-travel suspension not only provided an even ride but also better articulation. Range Rovers kept their wheels in contact with the earth. Any that lost touch had no traction.

I took pictures of Blunsden demonstrating it. On wet rocks, potholes 2ft deep from crest to crest, wet sand, loose boulders, clay and combinations up to gradients of nearly 1:1, he crawled the car out of craters. If one set of wheels lost grip, he operated a button locking up all four to prevent drive leaking away to one hanging in mid-air over a hole.

Range Rovers had a stirring road performance, swift acceleration and most of the tranquillity expected of a Rover. There was whine from transfer gears. Rover engineers assured us they would eliminate it, but never did. The Michelin X M+S tubed radial tyres howled a bit at 95mph but, like the rest of the vehicle, they were a revelation. Nothing this big and heavy had ever sustained this speed with such confidence, yet was still able to cope with flints and sharp rocks. At £2 short of £2,000 the new Range Rover seemed a bargain.

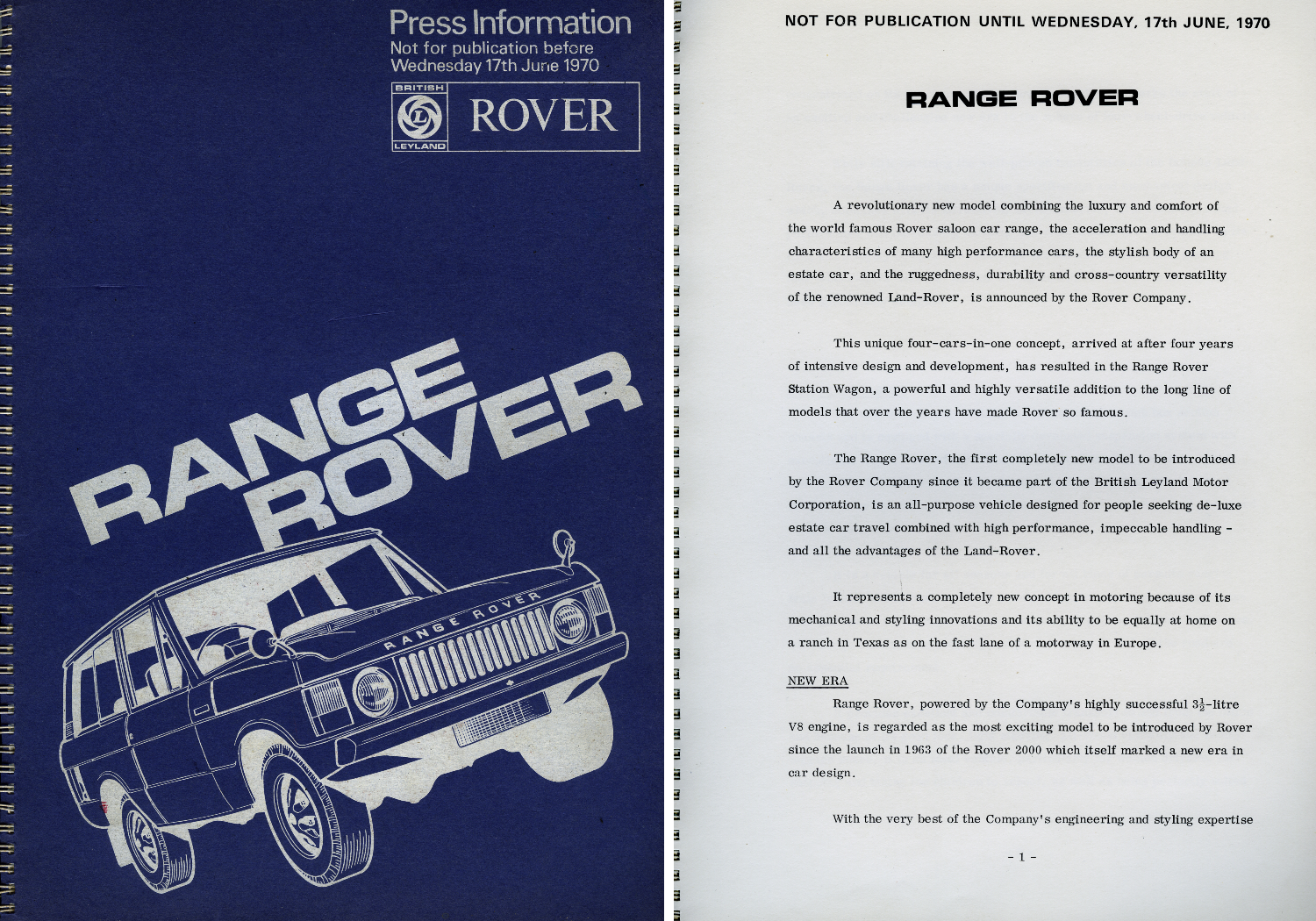

Aimed at a prosperous market that Bannock had identified for countryside pursuits, going on safari in comfort or simply looking squirearchical, it was cleverly styled and cleverly named. It was bigger and longer than regular Land Rovers, but not quite so tall, and you could see over a lot of traffic – a privilege not afforded to lower-order saloon drivers.

The interior was well laid-out. The company had planned it to be as luxurious as Rover cars, but the walnut veneer and the carpets had to wait. Practicality took precedence. With a rare display of publicity skill, Rover claimed the thick plastic floor covering had been designed from the start to be washed down with a hose. Gentleman farmers hadn’t wanted the trappings of a saloon, Rover told us. They were getting a car to drive in gumboots or city slip-ons, but that somehow would feel best in brogues.

“Nothing this big and heavy had ever sustained this speed with such confidence, yet was still able to cope with flints and sharp rocks”

The truth was that the interior design planning had gone badly and the hose-down story was a quick fix. We were impressed at the self-contained seats so firmly fixed they had their own integral seatbelts. Why, we wondered, had even safety legend Volvo not thought of that?

What we didn’t know was that these had taken so long to develop they nearly held up the entire launch. As it was, Rover’s press kit warned sternly: “Initial supplies of this vehicle will be restricted to the UK market. Further details of its international debut will be announced in a short time. To avoid disappointment by the general public it is essential that when reporting about this vehicle on the announcement day, it is made absolutely clear that even supplies to the home market will not start until September 1st. This delay will enable… “

We dutifully reported to the general public, and what a success the Range Rover was. King’s design work and Martin-Hurst’s discovery of a Buick V8 engine facing scrappage had been inspirational.

Blunsden and I went back to our motor racing and what a terrible year we had. Three weeks later I shared a lift to the Bouwes Palace hotel in Zandvoort with Formula One’s Piers Raymond Courage and his beautiful wife, Sarah Marguerite Curzon, thinking he had become a safer, more mature racing driver. He died in the race that weekend. Jochen Rindt won that cheerless Dutch Grand Prix, only to die himself in his Lotus that September, becoming F1’s posthumous world champion driver.

In the end I think I preferred road-testing.