Fuel company Ineos to work with Hyundai on hydrogen economy, Grenadier 4x4 fuel cell car

Ineos 'in a unique position to drive progress towards a carbon-free future based on hydrogen'

SOUTH Korean car maker Hyundai and fuel firm Ineos have signed a memorandum of understanding to speed up the global transition to a hydrogen economy, including work on a hydrogen-powered Grenadier off-roader.

The two companies, based in Seoul and London respectively, announced early this morning that they would focus on making hydrogen a viable option in Europe through both public and private sector projects, as well as evaluating the viability of using Hyundai’s existing hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) powertrain on the Grenadier, Ineos’ first vehicle, which closely resembles the old Land Rover Defender.

Ineos said that the collaboration marked a part of its efforts to “diversify its powertrain options at an early stage”. The British company is very much in its nascent stages as a car maker, having established itself as a juggernaut in the chemical industry.

In today’s press release, the company noted that it was well-placed to make the foray into FCEVs and hydrogen fuelling infrastructure due to the fact that it currently creates around 300,000 tonnes of hydrogen per year as a by-product of its chemical manufacturing operations.

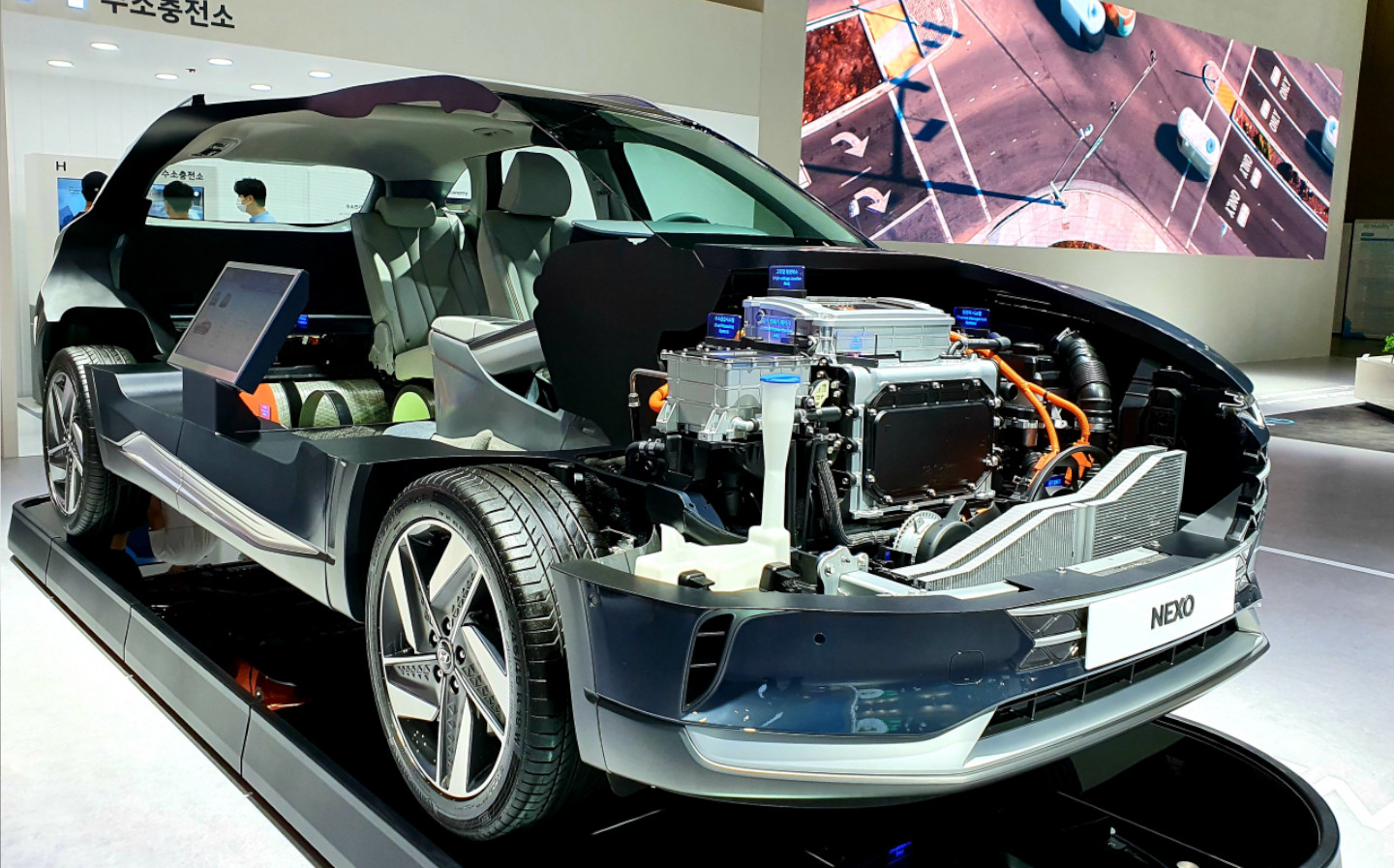

Most fuel cell vehicles carry between five and six kilograms of compressed hydrogen in a gas tank, which is then mixed with air in a fuel cell stack to produce electricity. That in turn powers the vehicle’s electric motor. The by-product is a small amount of H2O – water.

A subsidiary of Ineos called Inovyn is Europe’s largest operator of electrolysis, the process through which hydrogen is obtained for industrial and transportation use.

In a statement, the company said: “Our experience in storage and handling of hydrogen combined with its established know-how in electrolysis technology, puts Ineos in a unique position to drive progress towards a carbon-free future based on hydrogen.”

Last week the government outlined a £12bn “green industrial revolution” strategy that includes a goal of five gigawatts of hydrogen production capacity by 2030, to power industry, transport and homes, as well as the development of the first UK town heated by the hydrogen by the end of the decade. As part of the plan, new petrol and diesel cars will be banned from sale in the UK by 2030, with hybrids to follow five years later.

Hyundai has become an industry leader in the still relatively fledgling market for hydrogen-powered cars, alongside other Asian car makers such as Toyota and Nissan.

A hydrogen powertrain for the ix35, which the company claimed to be the world’s first production model hydrogen FCEV, was available in very limited numbers in the UK in 2015, and the Nexo, a £70,000 SUV built from the ground up as a fuel cell car, was released in 2018.

Getting hold of one is tricky, though – they are built to spec in Korea, which results in a lengthy wait. Fuelling them is tricky, too, with just 10 filling stations in the UK at present.

Nevertheless, the Ineos-Hyundai agreement revealed today could see the powertrain from the Nexo transplanted into the hydrogen Grenadier.

Ineos has built a reputation as something of an enfant terrible in its short time as a marque, due to the fact that the Grenadier SUV bears no small resemblance to the old-shape Land Rover Defender, and was revealed at broadly the same time that the all-new Defender hit roads.

The design so incensed Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), in fact, that it challenged Ineos’ design in the courtroom in an unsuccessful attempt to block the Ineos from coming to market. A judge ruled back in August that the shape of the old Defender was not “distinctive enough” to be trademarked by JLR.

How do hydrogen fuel cell vehicles work?

Similarly to the battery-electric vehicles that are becoming a larger presence on the UK’s roads, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are powered by electricity. However, while plug-in from car makers like Tesla take electricity from the Grid and store it in battery packs, FCEVs use an electrochemical reaction between hydrogen stored in the car’s fuel cell and oxygen in the air to create electricity, with the only by-product being water.

What advantages do FCEVs have over battery-electric vehicles?

As an electric car, FCEVs benefit from the impressive torque characteristics of electric motors – they are able to accelerate very quickly indeed. But FCEVs present several advantages when compared to battery-powered electric cars.

For example, the time a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle takes to refuel is broadly comparable to that of a traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) car — under ten minutes, whereas electric batteries can take many times that amount, even with the aid of a rapid charger.

Once fuelled, they also have excellent range: Toyota, for example, claims that its Mirai FCV has a range of more than 340 miles. Gas tanks are also much lighter than battery packs, meaning fuel cell cars feel more nimble.

It’s also estimated that FCVs are about 30% more environmentally friendly than their ICE counterparts, and two to three times more efficient.

What are the downsides of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles?

While there are unlimited amounts of hydrogen in the universe, obtaining it in a form in which it can be used in cars isn’t a particularly easy task. Most of the hydrogen produced today is created through a process called steam-methane reforming, which results in rather undesirable by-products such as carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, and can involve the use of fossil fuels. Although it is possible to do it in more environmentally friendly ways, that piles onto the cost of production.

And while refuelling with hydrogen is quick, and the range of FCEVs are high, there are very few places to refuel a hydrogen car — fewer than 20 in the UK. There are more than 20,000 public chargers for battery-electric vehicles, and that number is increasing rapidly. What’s more, those with private driveways can charge at home, overnight.

At present the cost of a fuel cell vehicle is extremely high, because demand is so low, and the cost of filling a tank is around £70, whereas a battery electric car can be refuelled for about £12, depending on the size of the battery pack and household energy costs.

Is the government investing in hydrogen infrastructure?

Last week, Prime Minister Boris Johnson set out the government’s “Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution”, which he claimed would create and support up to 250,000 jobs. There’s £12bn of funding attached to the plan, and the government hopes that it will spur private investment to triple by 2030.

The second of the ten points addresses hydrogen, with the government committing to work with industry to generate five gigawatts of low-carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030, for “industry, transport, power and homes”. It also said that it wanted to develop the first town powered solely by hydrogen by the end of the decade.

Back in February, Energy Minister Kwasi Kwarteng announced that £70m would be put towards funding two low-carbon hydrogen production plants in the UK, in Merseyside and Aberdeen.

In 2018 the government’s Office for Low Emission Vehicles (OLEV) announced the second stage of its £23m Hydrogen Transport Programme, with a proportion allocated to the funding of 10 new hydrogen filling stations. The previous phase saw £8.8m go towards four new refuelling stations and the upgrade of five existing stations.