Man vs machine: we race the Audi RS 7 driverless car (updated)

Driver, take a seat in the stands; this car races solo

WHAT SPECIAL genius did Ayrton Senna possess? Or Colin McRae? Was it their ability to see things that others missed — a split-second gap in the traffic ahead, for instance — or the natural courage to brake later, accelerate harder and turn in later? Or was it just that they were more consistent than the opposition: always in a near-perfect position on the track, relentlessly accurate?

Drivers still required: search for your next Audi on driving.co.uk

These questions are running through my mind as I storm through the infield section of the Oschersleben race circuit in northern Germany, darting left and then right and then left again. Hard on the brakes; harder on the throttle. The needle on the speedometer bouncing up to 100mph and then back down again as the car scythes through a tricky succession of bends.

The reason I am mulling over these things is that the car is not controlled by a human driver. I am in the passenger seat while the steering wheel twirls this way and that to place us perfectly on the racing line and computers decide exactly when to accelerate and brake. It is billed as the world’s fastest driverless car (although Driving rode around Laguna Seca racing circuit in a 150mph driverless BMW in 2011), and although the Audi engineers who built it are coy about making the claim, it has the potential to answer once and for all the question of what makes the perfect racing driver.

There is no human error with this vehicle: it never misses a gearchange, misjudges a bend or fails to accelerate quickly enough. Everything is programmed to result in the quickest lap possible. Think of it as a turbocharged, four-wheel-drive version of Deep Blue, the supercomputer that beat Garry Kasparov at chess in 1997.

“We hit a wet patch heading into one corner. The car slides on with a worrying lurch. But almost instantaneously the computer applies opposite lock and eases off the throttle to correct its line.”

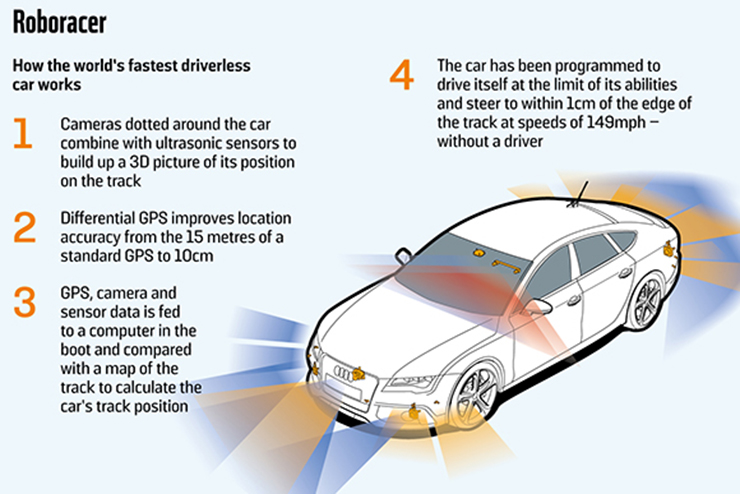

The technology that drives the “Audi RS 7 piloted driving concept”, to give it its full name, around the circuit is similar to that employed in guided missiles. But rather than being relied on to guarantee a designated target is hit at long range, it is used to ensure the car remains on the track at very low tolerances — Audi leaves itself a 1cm margin of error, not bad when travelling at 100mph or more.

The car does this by using the latest in GPS know-how, a battery of ultrasonic sensors like those used in modern parking assistance systems and a series of state-of-the-art stereo cameras mounted in the windscreen and rear window that constantly collect images of the track and compare them against graphic information of the circuit stored on board.

It is all controlled by a bank of computers in the forward section of the boot — a system Audi says it is in the process of miniaturising to ensure it can be fitted into production cars, which would be able to drive themselves at high speed on the road.

Audi claims that recent advances in the accuracy of GPS, as well as in sensor technology and computer processing functions that can replicate a driver’s actions, have taken the system tantalisingly close to production reality. They also allow Audi to program the car to operate at the very limits of its ability under racing conditions on a track.

The system is so smart it can compensate for the unexpected: on the track we hit a wet patch heading into one corner. The car slides on with a worrying lurch. But almost instantaneously the computer applies opposite steering lock and eases off the throttle to correct its line.

This would be impressive in any driverless car — but this is not an electrically powered Google pod with a top speed of 25mph . It is a 560bhp V8-powered RS 7. During my lap, we managed a maximum of 140mph, which, no matter how advanced the computer, was plenty fast enough with no driver behind the steering wheel.

So how good is it? Surely it can’t be better than a human driver, let alone a top-class racing driver. It was time to put on the old-fashioned racing gloves and helmet to find out.

Don’t know your BHPs from your MPVs? Click to take a look at our car jargon buster

The driverless Audi had managed a lap of the 2.3-mile circuit in 1 minute 57 seconds. Earlier, an Audi engineer had managed 2 minutes 3 seconds — slower than the driverless car by six seconds. By the time I climbed aboard an RS 7, albeit one that wasn’t weighed down with the banks of computers in the boot, and gunned the engine, I felt as if I had something to prove — not just to myself but also to drivers in general.

OK, I am hardly the driving equivalent of Kasparov, who accused the computer of cheating after losing the second game in the 1997 match, but I still like to believe that there is something instinctive, artistic even, in lapping a racing circuit. As any track-day enthusiast knows, there is a poetry of motion in a perfect lap, where everything seems to come together, and that a machine surely could not match.

I point the Audi down the long main straight and hit the timing beam with a heavy load of revs in seventh gear. Arriving at the first bend, I remember the computer-driven car. programmed to remain just within the track limits and not to stray even the slightest beyond them, took a fairly conservative entry line. I decide against this, placing the RS 7 as far as possible to the right and then ride the kerbs on the exit, just as Senna might have done.

The track is drier than when the driverless version took it on, so I’m able to brake later, carry more speed through corners and get on the power earlier. Maybe it is because I’m in control, but there feels to be greater smoothness and flow to the way the car laps the circuit. With the computer “at the wheel” the steering inputs felt more abrupt and it seemed to take a long time to accelerate out of corners.

Search for and buy a used Audi on driving.co.uk

Finally, I come to rest and a gaggle of Audi engineers and boffins huddle around a laptop to compare my time. I had managed a lap in 1 minute 52 seconds, shaving five seconds off the machine’s time.

The engineers are crestfallen and tell me that the track conditions were better for my lap because it was drier, which is true. But it still sounded like a line lifted straight out of the Racing Driver’s Book of Excuses. Perhaps machines learn quickly after all.