The heroes and harebrained: men and women who shaped British motoring

Why this lady carried a gun in her glovebox

IN 1900 there were just 8,000 cars in Britain. By 1920, there were more than 100,000 in London alone. Behind this surge in ownership were a legion of men and women who pushed the boundaries of creativity, bravery and – often – stupidity.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography lists more than 60 motoring pioneers who helped drive the development of the motor car, and who tell the story of an era when the lorry still had to be invented, when nobody had ever driven at 100mph, and when asbestos brakes were considered a good idea.

But the accounts also reveal that many of the themes were as familiar as they are now: ruses to avoid police speed traps, campaigners raging against profiteering petrol firms and road taxes, and disputes over whether women make good racing drivers.

Below are extracts from 10 little-known but hugely significant men and women who helped shape British motoring.

George Johnston, 1855-1945

From breadmakers to Britain’s first motor car

An apprentice locomotive engineer from Glasgow, George Johnston began his own business in 1882 making a “doughing machine” which cut dough into loaves, ready for baking before deciding that cars were more exciting. Johnston began designing his own engine and, with the help of two other engineers, in 1895, he was the first person to build a motor car in Britain.

Not that anybody would have recognised the name: it was known as either a “Benzoline” or petrol “dog cart” and was driven for the first time in November 1895 at 12 miles an hour on a 20 mile trip across Glasgow.

Having given his vehicle the name Mo-Car and won backing from Sir William Arrol, a Glasgow engineer, Johnston began selling the contraption in 1896 for £300 – £500, badged Arrol-Johnston. The venture was not a success. His partners left and a devastating fire destroyed the Johnston’s tools, cars and plans. The business was sold in 1905.

Another attempt at founding a car company failed two years later and Johnston was declared bankrupt.

William Rees Jeffreys, 1871-1954

The man who invented the M25

As secretary of the Road Board between 1910 and 1918, William Rees Jeffreys was responsible for spending motoring taxes on constructing and improving roads, but some of his greatest ideas were not implemented for several decades. After proposing a Great West Road, running from London to Bristol, it took almost 25 years for the first section to open. It eventually became the modern A4.

His other ideas weren’t implemented until after his death. It wasn’t until 1966 that his plan for a road crossing across the Severn river, between England and Wales, was built, and his visionary plans for “special roads restricted to motor traffic alone with no stopping permitted and no pipes or cables laid beneath them” did not arrive until 1958 when the first motorway, the Preston bypass in Lancashire, was opened. His orbital London by-pass became the M25 and was only completed in 1986

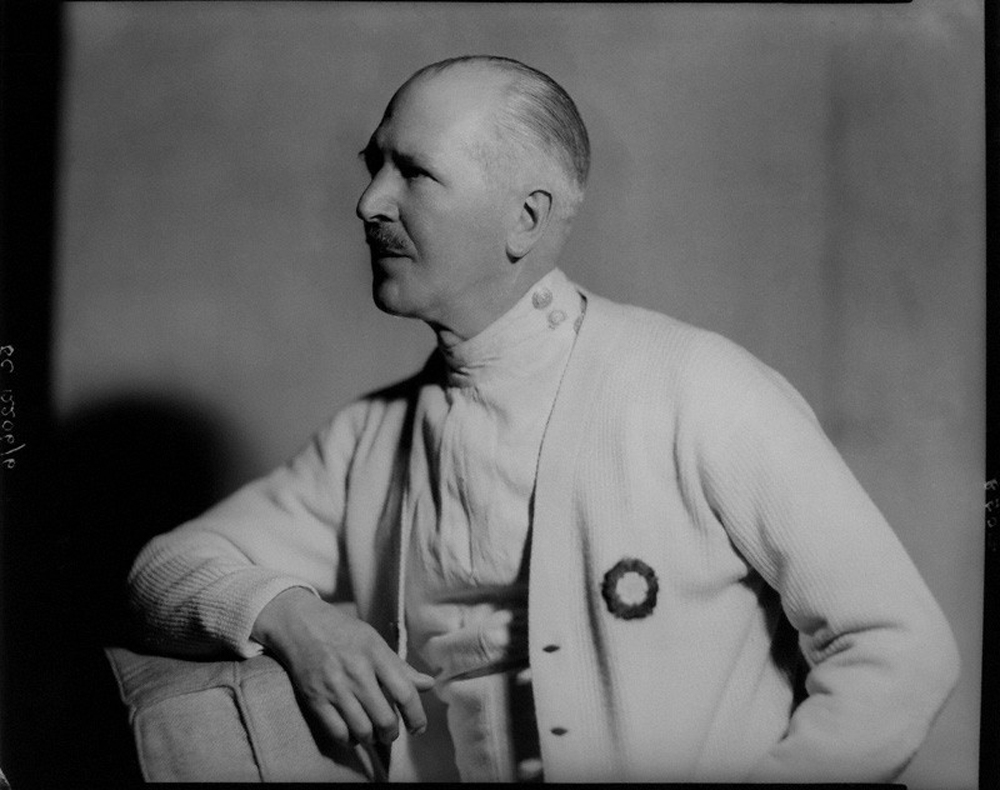

Sir Stenson Cooke, 1874-1942

Devised an early speed trap warning system

Captain Gatso may be the best known opponent of speed cameras, but he’s just the latest campaigner to follow in the footsteps of Sir Stenson Cooke who made speed trap avoidance an art.

Cooke became secretary of the Automobile Association (AA) in 1905 when it had around 90 members and £100 in the bank. By the time that he left, it had more than 720,000 members and 4,000 employees.

Part of the reason was his work warning members of police speed traps. At first, Cooke organised bicycle and motorbike patrols to locate speed traps and then warn members (identified by a badge on their car’s grille). It only took four years until the practice was ruled illegal.

But Cooke had a solution. He told the AA patrols to refrain from their customary salute when they passed members if a speed trap was close by, providing a warning by default. It was a move that is thought to have saved thousands of pounds in speeding fines.

Dorothy Elizabeth Levitt, 1882-1922

First British female racing driver who carried a revolver in her glove box

A secretary for the Napier Car Company from Hackney, London, Dorothy Elizabeth Levitt was singled out by a company director to train as a driver and mechanic because of her good looks. She was an irresistible marketing opportunity for the firm, who made her the first British woman to compete in a motor race in 1903.

It quickly became apparent that she was no novelty act, taking her first victory later that year. In 1905, she set the record for the “longest drive achieved by a lady driver” for a journey from London to Liverpool and back again.

She set a new world speed record for women of 91mph at Blackpool, earning her the nickname, “The fastest girl on Earth.”

Her fame meant that she was the first choice to dispense motoring advice to women, and she is reported to have taught Queen Alexandra, wife of King Edward VII, and the Royal Princesses how to drive.

In her 1909 book, The Woman and the Car: a Chatty Little Handbook for All Women who Motor or Want to Motor she advised women to carry gloves, chocolate, and a revolver in the drawer under the driver’s seat. She also recorded the first use of a rear-view mirror, suggesting that women use a long-handled mirror to look behind the car.

Sadly she disappeared from public record around 1910 and was found dead in her Marylebone house on May 17, 1922 due to “morphine poisoning while suffering from heart disease and an attack of measles,” according to the death certificate. An inquest recorded a verdict of misadventure.

Francis Curzon (fifth Earl Howe), 1884-1964

Motoring campaigner who blamed pedestrians for crashes and took up racing after being caught speeding

Elected Conservative MP for South Battersea, London, in 1918, Francis Curzon was the first motormouth, arguing passionately in favour of drivers’ rights. He accused petrol companies of profiteering and claimed that drivers were persecuted by police and unfairly taxed (sound familiar?).

He also called for the removal of the 20mph speed limit and complained that taxi drivers were responsible for congestion in London. In 1945 he blamed most of the 44,307 road deaths during wartime on “the recklessness of pedestrians”.

He had plenty of experience of “police persecution” himself, racking up 21 convictions between 1908 and 1924, despite making impassioned defences: when charged with driving at 32mph in a 20mph zone, he said, “the car had four wheel brakes and could pull up very quickly.”

Eventually in 1928, fed up with seeing him in court, a magistrate told Curzon to take up motor racing. Aged 44, he took up the sport, competing at Le Mans and Brooklands, which resulted in little success but spectacular crashes.

Louis Vorow Zborowski, 1895-1924

The man who inspired Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

Born in Mayfair, Louis Vorow Zborowski wanted to be a racing driver, despite his father’s death in a racing accident in 1903.

He took advantage of the large number of aeroplane engines available at the end of the Second World War to build his own car, dropping a 23-litre Maybach engine from a Zeppelin airship into a boxy bodyshell. The car was named Chitty Bang Bang and won its first race at Brooklands in 1921.

Among the spectators that saw it race was Ian Fleming, the novelist who incorporated the car into his children’s story: Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang. By the time it was published, Zborowski was dead, killed during the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, on October 19, 1924, when his car skidded off the track and hit a tree.

Ernest Eldridge, 1897-1935

Expert at combining a plane and a car

Ernest Eldridge’s philosophy to car building was simple: take an engine from a First World War plane and jam it into a vehicle.

The approach won him a land speed record in 1924 from behind the wheel of Mephistopheles powered by a 260bhp Fiat aeroplane engine. The 146.01mph record was the last to be set on a public road.

Albert Durrant, 1898-1984

Designer of the Routemaster: the most famous bus in the world

Albert Durrant created the London Routemaster which is still in use in the capital today. He joined the London General Omnibus Company in 1919. By 1935 he was the chief engineer for buses and coaches and London Transport, where he had the responsibility of designing a new bus to replace the capital’s trolleybuses.

The first version, the RT, included novel components like power steering and air powered brakes. The Second World War saw him designing tanks before he returned to London Transport to lead the team that created the Routemaster.

Designed to be narrow enough for London’s streets, and with a large number of interchangeable parts to make production and repairs cheap, the bus also had features like an automatic gearbox, independent springs and heating controls, as well as the technology from the RT.

The bus was still in active service 20 years after he died and is still used on two routes in London. A new Routemaster was launched in 2012.

Violette Cordery, 1900-1983

Female racer who showed women could not just equal but surpass male achievements behind the wheel

Eight years before women had the same voting rights as men, Violette Cordery began her motor racing career, leaving a line of male rivals in her dust.

She became a specialist in setting speed and endurance world records for Invicta sports cars, to prove their reliability. One of her biggest tests came when she travelled to Monza, in Italy, to set a long distance record, leading a team of six drivers (five of them men) to drive 15,000 miles at an average speed of 55.76mph.

She then took an Invicta around the world, driving through Europe, Africa, India, Australia, the United States, and Canada at an average speed of 24.6mph before returning to the circuit, driving 30,000 miles round the Brooklands track in Surrey in 30,000 minutes.

But despite all of her feats, the road to female emancipation had not reached the finish line. She retired from racing when she got married in 1931.

Albert William Denly, 1900-1989

Butcher’s boy turned world record holder

One of the greatest motorbike riders of the era was discovered working as an apprentice to a butcher in Surrey – and only because he used to deliver meat on his Douglas motorcycle.

Local magistrates were the first to notice Albert William Denley’s speedy riding, but along with the admonishments came recognition from an engine tuner working at the nearby Brooklands circuit.

Denly began working as a test rider for Norton Brooklands engines in 1923 and began entering races. He won his first race on a 500cc Norton three months later, then began setting world records for the bike manufacturer, taking more than 110 in his first three years.

In his eight years as a factory team rider, the butcher’s boy took more than 300 records.